Much faster than our last one.

From November 2 to 6 , Br. Benedict attended a Visitation Conference at St. John’s Chapter House in Collegeville, Minnesota. The workshop he participated in prepared at least 12 monks from many abbeys to be visitators to 20 abbeys in the American Cassinese Congregation of which we belong. A visitator spends about a week at an abbey interviewing the monks and membeFrom November 2 to 6 , Br. Benedict attended a Visitation Conference at St. John’s Chapter House in Collegeville, Minnesota. The workshop he participated in prepared at least 12 monks from many abbeys to be visitators to 20 abbeys in the American Cassinese Congregation of which we belong. A visitator spends about a week at an abbey interviewing the monks and members and then giving an evaluation, after discussion, to the abbot and to the community. This information is then sent to the abbot president for further evaluation and discussion. Some suggestions are made like, what should happen to retired priests who have just returned to the abbey or how the community could better help the new candidates and novices.rs and then giving an evaluation, after discussion, to the abbot and to the community. This information is then sent to the abbot president for further evaluation and discussion. Some suggestions are made like, what should happen to retired priests who have just returned to the abbey or how the community could better help the new candidates and novices.

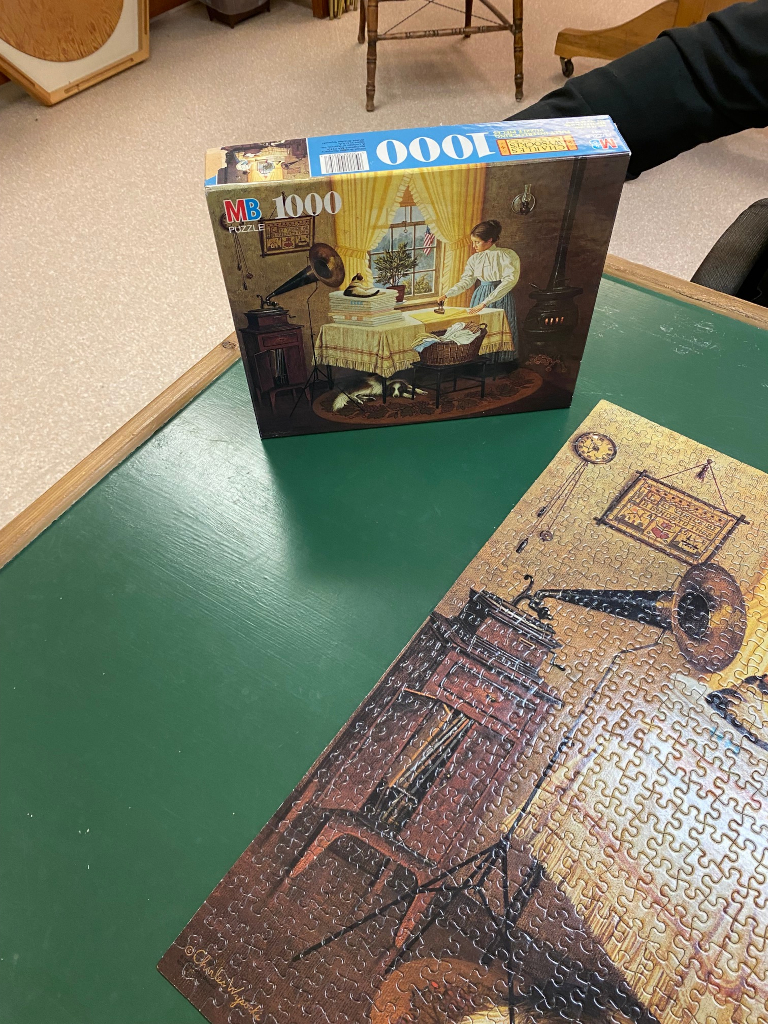

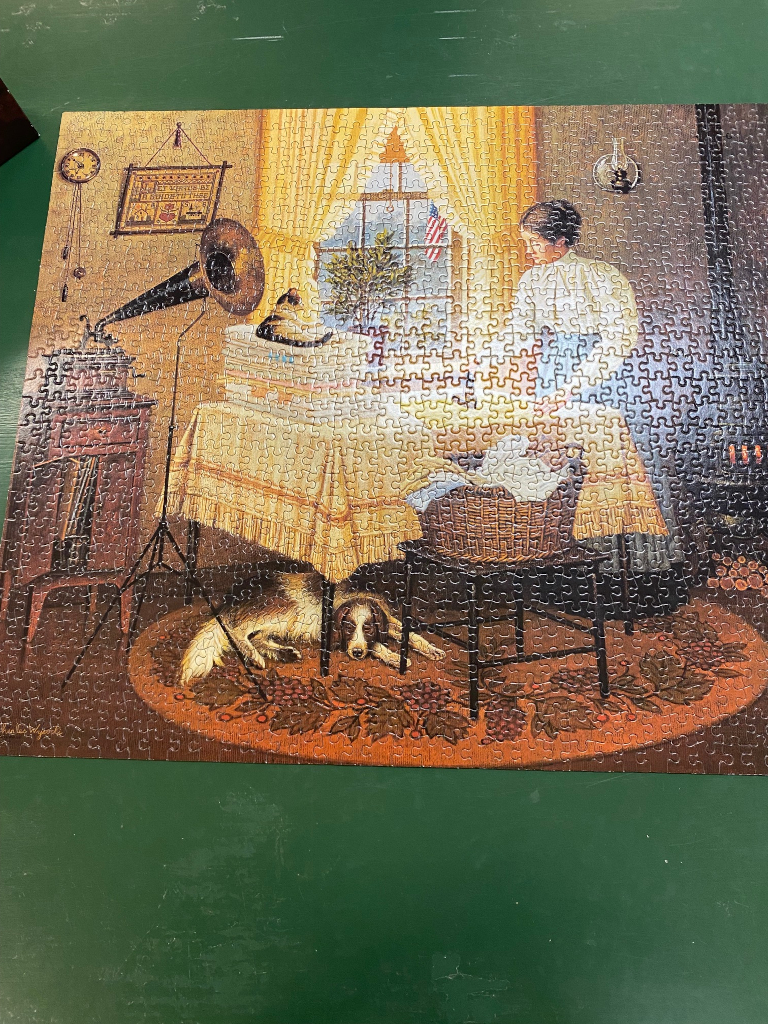

Here are two photos of our south view from the church hallway taken about 9:45 am this morning. The next two photos were taken about 5:25pm from the same window. I hope that the Winnipeggers don’t get snow

this weekend.

I went shopping for some things and even though the temperature was only zero, we had a blizzard and I had to drive seventy on a hundred maximum highway.

Have a safe and enjoyable day tomorrow!

Peter (Brother Benedict)